Richard Ha writes:

We’re planning to landscape the area around our new hydroelectric system with canoe plants, the plants that the first Polynesian settlers brought with them from their previous island homes to help them survive and thrive in their new land.

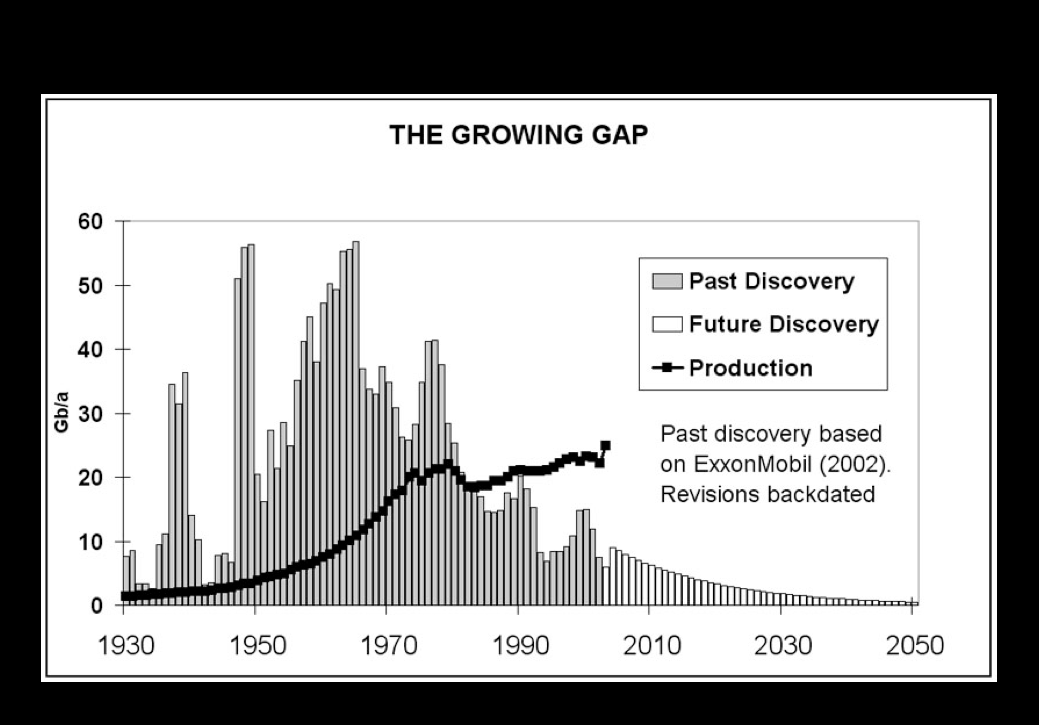

They were the original organic farmers. They had no oil back

then, of course, so no oil technologies.

And they did not just survive in their oil-free lives, but thrived and supported a large population here well (research suggests it was a

population as large as we have now).

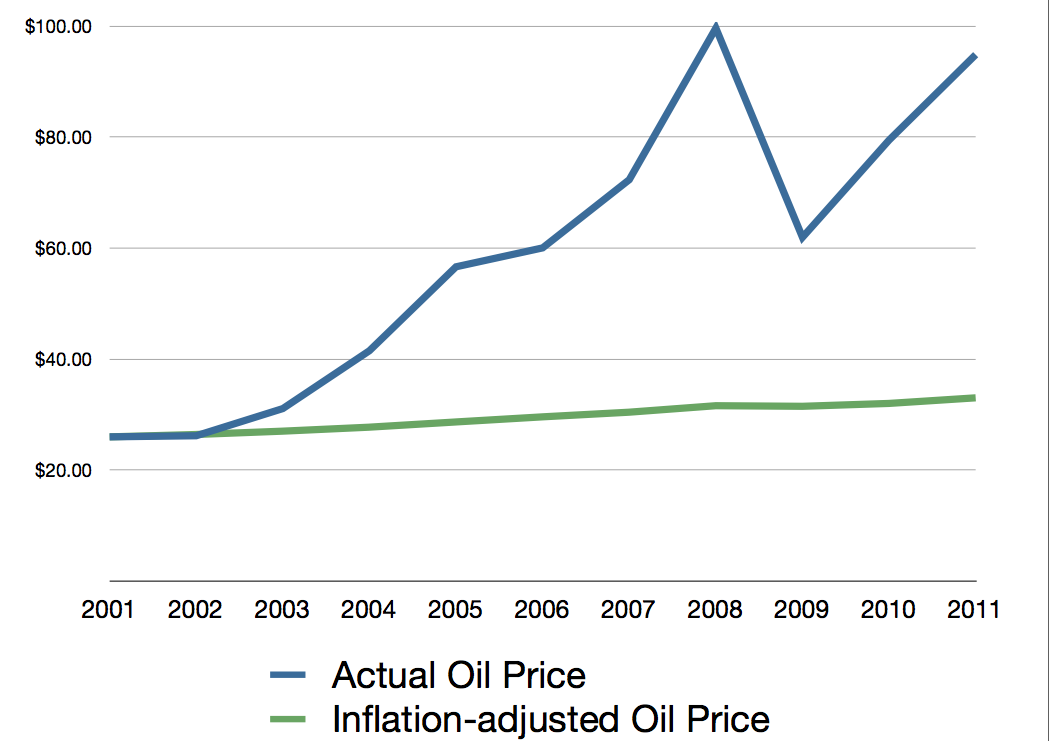

So as we reach the age of Peak Oil, the end of easy and cheap oil and all that came with that, I want to explore how they did it. I

want to learn from them and see what, from those times, we can focus on again to improve our lives now. Our hydroelectric system is another example of what we are doing in these regards.

There are still people, of course, who have always lived

with the old ways, and who continue to do so. I met some people at the Hawai‘i Community College who are perpetuating this culture and who have offered to help me. I’ll write more about that soon.

For now I thought I’d revisit what we know happened on this

land before we started farming it. A lot of this information comes from the Cultural Resources Review of our poperty done by the USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Our farm encompasses three ahupua‘a in the district of South Hilo:

1. Ka‘upakuea at the north (bordered at the south by Makea Stream).

We don’t know much about what went on in Ka‘upakuea before the mid-19th century. In the mid-1800s, both Ka‘upakuea and Kahua were government lands, which were lands Kamehameha III gave “to the chiefs and people.” Ka‘upakuea was part of Grant 872. (Read the 1882 document A Brief History of Land Titles in the Hawaiian Kingdom for more on Hawai‘i’s historical land system.)

The area was later part of a sugar plantation, and has unpaved roadways and a west-east flume. Kaupakuea Camp was within the area of what’s presently our farm.

2. Kahua (which is between Makea and Alia Streams).

Kahua is a very narrow ahupua‘a, approximately 600 feet wide. It extends from the coast to about Makea Spring, which is at about the 980 foot elevation.

Kahonu (an ali‘i who was descended from both the I and Mahi

lines of chiefs, and who was in charge of the Fort at Punchbowl ca. 1833-34) was awarded either the whole of Kahua ahupua‘a or just the northern mauka half of it (references differ) as LCA 5663.

When he died in 1851, his relative Abner Paki (father of

Bernice Pauahi and hanai father of Lili‘uokalani) held the lands “under a verbal will from Kahonu” (Barrère 1994:138). When Paki died in 1855, the lands were listed as Bishop Estate lands.

3. Makahanaloa at its southern edge (bordered by Alia and Wai‘a‘ama Streams).

The ahupua‘a of Makahanaloa (Maka-hana-loa) runs from the coast about 3.5 miles up to the 6600-foot elevation. Kapue Stream flows from the base of Pu‘u Kahinahina down through Makahanaloa. Magnetic Hill is at the southwestern corner at the top of the ahupua‘a, which is a little over a mile wide and meets the North Hilo district boundary.

In the Great Mahele of 1848, 7600 acres of Makahanaloa and

Pepe‘ekeo were awarded to William Charles Lunalilo (an ali‘i who later became king, from 1873 until his death in 1874). Upon his death, his personal property went to his father Charles Kana‘ina.

Here are a couple of interesting facts about Makahanaloa

ahupua‘a: Somewhere within this area, though the exact location is unknown, there was (is?) an “ancient leaping place for souls.”

And according to historian Mary Kawena Pūku‘i, a sacred bamboo grove called Hōmaika‘ohe was planted at Makahanaloa by the god Kane. “Bamboo knifes used for circumcision came from this grove,” she wrote.

Sugar cane was one of the canoe plants; it came with the early Polynesians to Hawai‘i and they used it as food and sweetener, and chewed it to strengthen their teeth and gums.

The farm sits on land that was formerly part of a sugar plantation that had its origins in 1857, when Theophilus Metcalf started Metcalf Plantation. After his death in 1874, the 1500-acre plantation was purchased by Mr. Afong and Mr. Achuck and its name changed to Pepeekeo Sugar Company. In 1879, they also acquired the 7600-acre Makahaula Plantation. By 1882, both were combined as Pepeekeo Sugar Mill & Plantation. In 1889, Afong returned to China, leaving the plantation in the hands of his friend Samuel M. Damon.

Over the years, it changed hands several more times. C. Brewer

& Co. bought the plantation in 1904, added a plantation hospital and improved housing. By 1910, plantation fields were connected by good dirt roads and harvested cane was delivered to the mill by railroad cars and stationary flumes.

Post-1923, the plantation improved its soil every year by adding coral sand (from Wai‘anae), bone meal and guano. “The sand was bagged and hauled into the fields by mules to be spread” (Dorrance & Morgan 2000:101). Eucalyptus trees were planted as windbreaks, protecting the fields near the ‘ōhi‘a forests.

Water came from Wai‘a‘ama Stream and Kauku Hill.

Plowing was

done to 18 to 20 inches. After 1932, tractors with caterpillar tracks were used for plowing. From 1941, trucks hauled harvested cane to the mill.

In the early 1950s, lots and houses on the plantation were sold to residents.

Under C. Brewer, there were several mergers: Honomu Sugar Company in 1946; Hakalau Sugar Company in 1963; consolidation of Wainaku, Hakalau, Pepeekeo, and Papaikou sugar companies in 1971, and a final merger in 1973 with Mauna Kea Sugar (once 5 separate plantations: Honomu, Hakalau, Pepeekeo, Onomea and Hilo Sugar Company) to form Mauna Kea Sugar Company, the state’s largest with 18,000 acres of cane (Dorrance & Morgan 2000:104).

Prior to the final merger, Mauna Kea Sugar Company had formed

a non-profit corporation with the United Cane Planters’ Cooperative, the Hilo Coast Processing Company, to harvest and grind sugarcane.

The Hilo Coast Processing Company and the Mauna Kea Sugar

Company (at that point called Mauna Kea Agribusiness Company) mill shut down in 1994.

We started farming on this land in 1994.

I’m very interested in knowing more history about this place. If you or your family know old stories about this area, I would love to hear them.